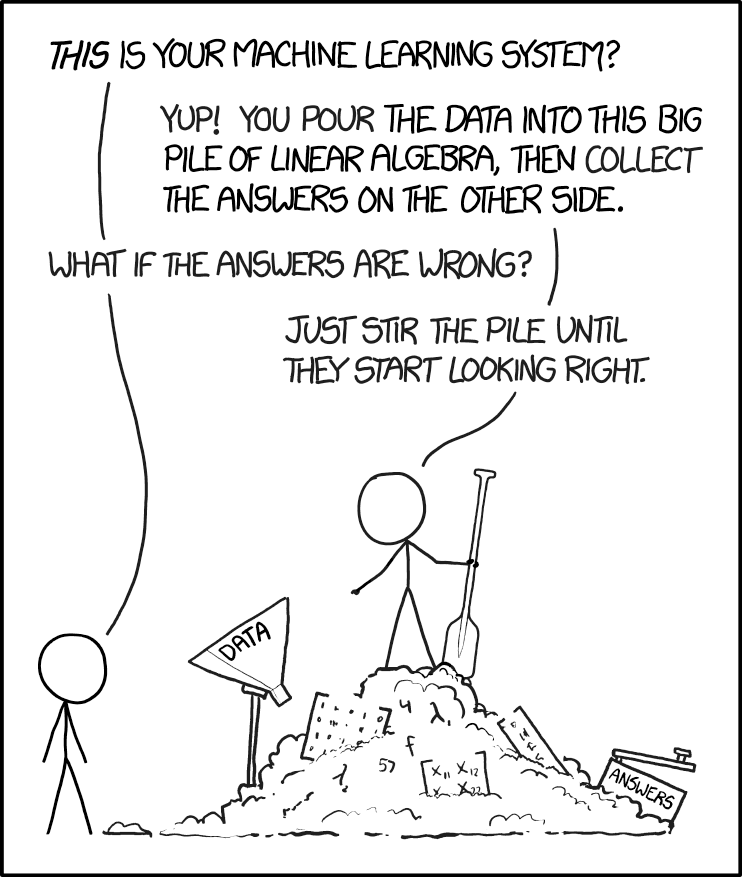

While I was visiting with my aunt the other day she asked me, “what is machine learning?” I was caught off guard because the term is so common place in my work that I hadn’t really tried to explain it as simply as possible before. I normally think about Machine Learning (ML) as a collection of statistical and mathematical techniques to analyze and draw inferences from patterns in data. While it’s not required to be considered machine learning, I also almost always also think of the variance-bias trade-off. Neither seemed to be of much help when talking with my Aunt. Perhaps my favorite explanation is from xkcd:

The variance-bias trade-off

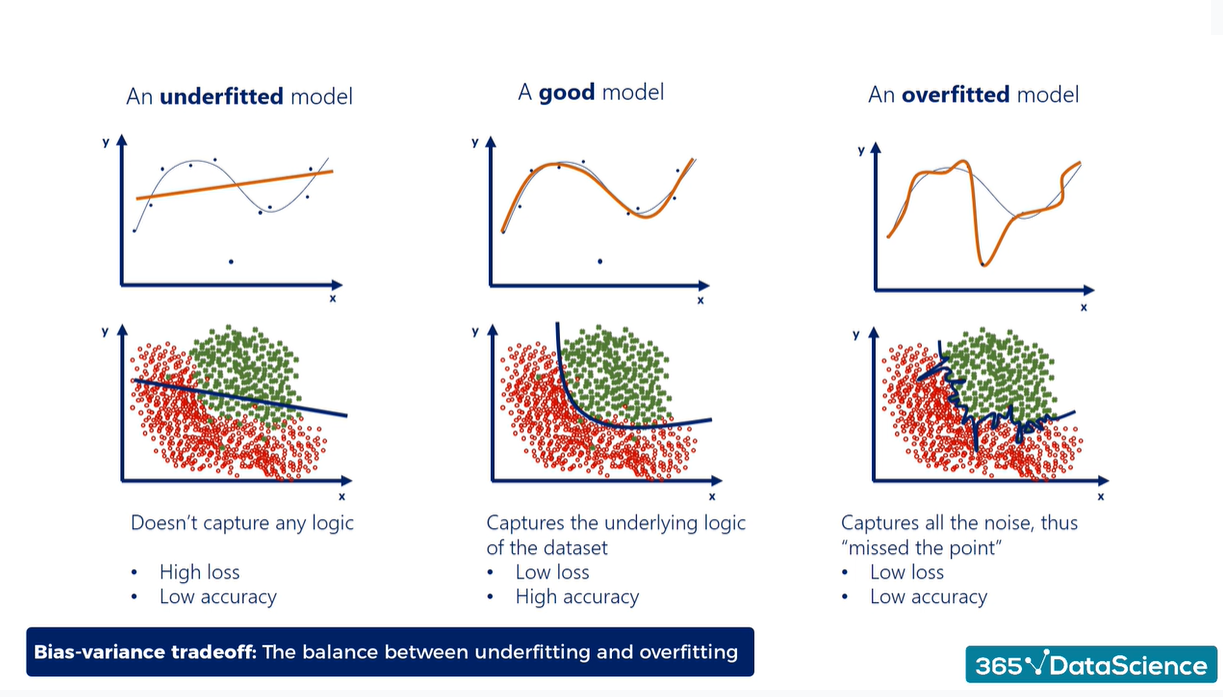

I think the bias-variance trade-off is a good place to start. It’s an important concept that describes the balance between two sources of error that affect model performance: bias and variance. Bias refers to the error introduced by simplifying assumptions made by the model, leading to systematic inaccuracies or underfitting. Variance, on the other hand, represents the model’s sensitivity to fluctuations in the training data, causing overfitting.

An optimal model minimizes the total error by striking a balance between bias and variance. Too much bias results in an overly simple model that misses relevant patterns, while too much variance creates an overly complex model that captures noise rather than the underlying data structure. Finding this balance is important for both classification and regression based problems.

Unfortunately the ‘sweet-spot’ between bias and variances depends on how much data you have.

But how do we control where we land on the variance-bias trade-off? In short, by changing the flexibility of the model. This is often done by turning the levers, switches, and dials in our model fitting method to ramp up or ramp down model complexity in different ways, hunting for the perfect balance between bias and variance. For tree-based methods like boosted regression trees this could, in example, involve controlling the maximum tree depth. But how do we find the best level of model complexity? One way is by holding back a part of our data to tune against.

The train-validate-test split

Using a train-validate-test split ensures that models generalize well to new data. By splitting the data into three sets, we can effectively train the model on the training set, tune hyper-parameters and make decisions on model performance using the validation set, and finally, evaluate the model’s performance on a hold-out test set. The splits look like this in tidymodels:

A downside is that we set aside parts of the data twice, reducing the amount of data available for training. Techniques like cross-balidation help to avoid reducing the amount of data too much by allowing all data points to be used for both training and validation. Instead of splitting off a single validation set, cross-validation partitions the data into multiple subsets and trains the model on different combinations, each time validating on the remaining subset. This method ensures that every data point is utilized for validation without significantly reducing the training data size and, as a bonus, prevents outlier datapoints from unduly influencing hyper-parameter selection.

My definition

Not all methods require hyper-parameter tuning. Heck a simple linear regression technically is a type of supervised machine learning. Ultimately though, I think of Machine Learning as a branch of artificial intelligence that consists of any computational process capable of improving it’s answers over time. Instead of following a fixed and rigid method, machine learning algorithms analyze data to identify patterns and use those patterns to improve their performance. That could either be through the addition of more data to train on or a more refined set of hyper-parameters that increase the efficiency of model training. In the xkcd comic above not only do the answers that come out of the box become refined (hopefully!) when you pour more data in but it also becomes a pile that stirs itself. And a good sign you’re dealing with an ML based approach is if you see that train-validate-test split or hear the words ‘cross-validation’.

But why would you want to use ML anyway? Definitely any time you want to use a complex model to predict out-of sample. When you wouldn’t want to use ML methods? Maybe if you’re interested in the noise or you just care about deeply describing your particular dataset and not predicting outside the range of your data.

I would love to hear your thoughts! What are your general definitions of Machine Learning for a non-expert audience? When should you use, or avoid using, ML methods?

Be well.